|

|

![James Joyce após mais uma operação aos olhos - foto no sul de França, 1922 [Rosenbach Museum and Library]](https://www.deficienciavisual.pt/Quadros/James_Joyce-apos_mais_1_operacao_aos_olhos-sul%20de%20Franca-1922-foto%20Rosenbach%20Museum%20and%20Library.jpg)

James Joyce - após mais

uma operação aos olhos - no

sul de França, 1922

In view of the apparent conception of James Joyce as a blind bard and the corresponding stock remark

that his compensatory aural acuity largely informed his ultimate novel, the neglected fact that

Joyce clearly belongs to a tradition of blind bards, including Homer, Dante, and Milton, calls for critical recognition. An additional reason for uncovering the promising field of thematic

blindness lies in the advantage of joining together various autonomous aspects of Joyce

scholarship, such as the theory of the senses, the notions of prophecy and epiphany, and the

question of the father-son reconciliation that lies at the heart of Joyce’s 1922 novel.

Rather than formulating a general taxonomy of possible case-studies and research methods, the present study consists of various preliminary explorations of a relatively new field of

study. By focusing on the literary resonances of Joyce’s defective eyesight and correlating the

(prophetic) implications of his near-blindness with the literary tradition of the blind prophet, we can extend in both time and space the critical parameters of Joyce scholarship, thereby

adding new dimensions and unforeseen interrelationships to the extensive critical industry of

James Joyce.Let me state beforehand that an adequate treatment of the literary work of James Joyce, in

particular his later prose fiction, Ulysses and Finnegans Wake, would require far more space

than can be given here. Following some characteristics of the Dutch critical reception of

Joyce, I largely “favour a non-theoretical approach in which close reading takes centre

stage.” In the light of my original intention to unearth a relatively new field in Joyce

scholarship, I therefore merely expect to work in a preliminary fashion, since “[t]o attempt to

do more than scratch the surface of […] Finnegans Wake, [for example,] would clearly

exceed any reasonable limits of time and space.”

Irisitis

The present study starts from the relatively simple premise of regarding the ocular disorder

Joyce developed during his life as a clear influence on Ulysses and Finnegans Wake,

epitomized by the striking correspondence between sign and reference in the case of ‘irisitis.’

Although the common designation to describe an inflammation of the eye is ‘iritis,’ a word

generally employed by Joyce and the majority of his critics to refer to the writer’s eye

troubles, the alternative spelling ‘irisitis,’ an etymologically more exact orthographic

rendering to be found in nineteenth-century medical lexicons, constitutes a proper

denominator for the subject at hand, simultaneously conveying a distinct sense of Joyce’s

textual play and extreme use of polysemy. Linguistically speaking, the word ‘irisitis,’ a

derivational compound made up of the originally Greek morphemes ‘iris’ and ‘-itis,’ contains

three unstressed syllables next to the stressed penult. Apart from the denotation of ‘irisitis,’

which refers to the inflammation of the colored part of the eye surrounding the black pupil,

the term obviously echoes two defining elements in the life and art of James Joyce, namely

his distinctly Irish background and his progressive loss of sight. According to a homophonic

correspondence, the latter also echoes the (in)distinct historical geography of Ulysses and

Finnegans Wake and refers to the extensive intertextual references to be found in both works,

which have excited such a vast amount of intellectual despair.

Interestingly, the obsolete term as a whole sounds much like the self-referential

pronouncement “I recite this,” which denotes the predominance of sound and musical

qualities in both Milton’s poetry and Joyce’s later prose, a fact that prompted T.S. Eliot to

proclaim James Joyce the greatest master of the English language since Milton, whom he

considered mainly to be a writer for the ear. Contrary to the more common denomination for

the inflammation of the iris, iritis (read: ‘I write this’), which clearly accommodates

Gottfried’s genetic reading of and semiotic approach to Ulysses, the term ‘irisitis’ fully

characterizes Joyce’s compromised eyesight and eventual near-blindness that progressively

led him to dictate his ultimate novel to various assistants.

Milton

dita o Paradise Lost -

Eugene Delacroix, 1826

Immediately related to the deficiency of sight and greater musical ear of both Milton and

Joyce, ‘irisitis’ reads like a circular proposition, which designates the overall conjunction of

ear and eye in Ulysses and the Wake. When we suppose, in fact, that ‘irisitis’ consists of four

monosyllables that make up a pair of trochees, and the first word starts with a long Gaelic vowel, as exemplified by the phrase “talk earish with his eyes shut,” then the line would run

as follows: ear is sight is. Besides the fact that ‘irisitis,’ in this way, aptly summarizes the

tenor of our argument, it also successfully evokes the circular structure and infinitely

suspended last sentence of the Wake.

When viewed in the light of temporal/spatial relations, moreover, the proposition’s implied

modes of the audible and the visible, which Stephen Dedalus, following Schopenhauer’s

example, designates as respectively Nacheinander (an image of time) and Nebeneinander (an

image of space) in the “Proteus” section of Ulysses, immediately relate to Joyce’s

revolutionary poetical program.

Already questioning the basic assumptions of temporal and

spatial reality in his modernistic masterpiece, Ulysses, the linguistic cosmogony of Joyce’s

ultimate novel would infinitely expand the relatively narrow parameters of fictional time and

space. In “Circe,” for example, the invocation of Paddy Dignam’s servile ghost, who cannot

but respond to his master voice, prompts Leopold Bloom to remark triumphantly, “You

hear?” Echoing Dante’s startling encounter with his former mentor Brunetto Latini in the

seventh circle of hell, the passage alternately summons up the modality of the audible (time)

and the unity of place. Through the allusion to Dante, which transmigrates the scene and its

protagonist into the past, and numerous acts of metempsychosis, involving for instance the

image of a beardless William Shakespeare superimposed upon the reflection of Bloom and

Stephen gazing in the mirror, Joyce crosses the traditional boundaries of time and space, although Ulysses as a whole remarkably adheres to the neoclassical principles of dramatic

structure. It should be remembered that the polysemous affliction Joyce repeatedly suffered from

partakes of a general tendency of mistakes and contingencies in his personal life which he, as

a “man of genius,” deemed “volitional” and designated as “portals of discovery.”

As famously exemplified by Frank O’Connor’s anecdote about Joyce placing a picture of Cork in

a cork frame, Joyce’s lifelong attempt to “establish a direct correspondence between

substance and style” makes up one of his major artistic techniques. Accordingly, the

meaningful coincidence of irisitis illuminates the important relationship between form and

content in the literary work of James Joyce.

It is important to recognize, furthermore, that any artistic notion of chance Joyce may have

had, whether observing in his life meaningful coincidences or downright ‘luck of the Irish,’

presupposes an intricate relationship between life and art. To be sure, the personal events of

Joyce’s life are so inextricably woven into his work, that many believed his first novel,

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, to be a genuine autobiography. Even Joyce’s ultimate

novel, which exhibits an apparent meaninglessness in the verisimilitude of everyday life, has

been read by some as his confession and autobiography.

According to Thornton Wilder, for

example, “Finnegans Wake is […] an agonized journey into the private life of James Joyce.” As Roy Gottfried, among others, has amply demonstrated, the systematic uncertainty and

obscurity of Ulysses and Finnegans Wake run parallel to Joyce’s pathology. In this sense, the

notion of blindness can be seen as more than an analogy, since Joyce “wrote over every

square inch of the only foolscap available, his own body.”

Therefore, rather than attempting

to deconstruct life’s intricate relation to art, we will proceed instead from the basic

assumption regarding the significant mutual influence of Joyce’s personal life on the

development of his fiction.

Ultimately, the imperative mood of ‘irisitis’ (read: ‘Eye, resight this’) alludes to the notion

of second sight which, following the internal logic of a subsequently primary and secondary

order of vision, makes up the alternate, albeit related, point of departure for the present study.

On His Blindness

A further observation that has instigated the current research has to do with the tradition of the

blind, prophetic bard to which the historical figure of James Joyce arguably belongs. Extending

from Homer, with whom the blind bard has become synonymous, the literary tradition

of the blind seer or the sightless poet who has been accorded the gift of prophecy includes the

illustrious cases of Tiresias, “the Theban seer whose blindness proved his great

illumination,” and John Milton, the blind epic poet who turned blind in mid-life and

subsequently used his own biography to develop the theme of blindness in his literary work.

![O Cego Tirésias com um Rapaz - John Flaxman, c.18th [imagem Bridgeman]](https://www.deficienciavisual.pt/Quadros/The%20Blind%20Tiresias%20and%20a%20boy-John%20Flaxman-c18th.jpg)

O Cego

Tirésias com um Rapaz

John Flaxman, séc. XVIII

In his “Defence of Poetry” (1821), Shelley praised the latter as the third great epic poet after

Homer and Dante, and he closely connected Milton’s Paradise Lost with La Divina

Commedia. To be sure, it remains a singular fact that two of the three greatest epic poets of

Western literature were blind, while the third, Dante Alighieri, suffered from a considerable

visual impairment in his later years. When we consider, furthermore, the fact that the novel

has replaced the epic as the major literary form in English, as well as Georg Lukács’

definition of the novel as “the epic of an age in which the extensive totality of life is no longer

directly given,” the destiny Joyce shared with Homer, Milton, and Dante becomes all the

more intriguing. In this light, their respective blindness can be “interpreted as a threshold

between physical mortality and literary immortality.”

As stated before, the literary tradition of the blind bard originated with Homer, the Ionian

bard who has been credited with the authorship of the

Iliad and the Odyssey.

As Adaline

Glasheen puts it in her offhand way, “[i]t probably mattered to Joyce that Homer was

blind.” The extent to which Joyce was preoccupied with the striking analogy is difficult to

retrace, although, in any case, Joyce, in 1922, had to be reassured by his ophthalmologist Dr.

Borsch that there was no imminent danger of glaucoma foudroyant, “the disease which […]

was probably the cause of Homer’s blindness.”

A

Apoteose de Homero -

Ingres, 1827

By itself, the ancient life of “[b]lind Melesigenes, thence Homer call’d,” interwoven with

mythography and ancient popular etymology, remains a matter of strong controversy. Even

though it has been virtually impossible to retrace the original author of both epics handed

down by oral tradition, the cultural archetype of the blind bard nonetheless has firmly taken

root in Western literature. Whether or not Homer, in his rendering of Demodocus, utilized his

own sightless experience, the blind bard who recites in the eight book of the Odyssey a couple

of Ulysses’ adventures, including his ploy of the Trojan horse, has constituted the age-old

association between the topic of blindness and the inward vision of the bard.

In Derek

Walcott’s epic poem Omeros (1990), for example, the rich allegory of the blind poet is

celebrated in the title character, who possesses the gift of inner vision. In particular, Homer’s

St. Lucian avatar, a blind old sailor named Seven Seas, presents “a fascinating genealogy

composed of Homer, Demodocus, Joyce, as well as distant echoes of the mythical figure of

the blind Argentine poet, Jorge Luis Borges.” When James Joyce, in a discussion with his language pupil Georges Borach in 1917, answered for his lifelong preoccupation with Homer’s Odyssey, he observed that “[t]he most

beautiful, all-embracing theme is that of the Odyssey. […] Dante tires one quickly; it is like

looking into the sun.”

Interestingly, Joyce’s observation regarding the blinding effect of

Dante’s literary work precisely echoes the great symbolic value the latter attaches to light, darkness, vision, and blindness in his Commedia. In the twenty-fifth canto of Paradiso, for

instance, Dante loses his sight when he looks into the luminous presence of St. John the

Evangelist. In the following canto, the eventual restoration of his sight by Beatrice ends the

account of his examination by St. John on the virtue of love. In the thirty-second canto of

Purgatorio, the pilgrim Dante is likewise temporarily blinded, when he stares, for the first

time in ten years, into the face of Beatrice. Subsequently, “her enamelled eyes” transmit the divine light that in effect will raise Dante to the first sphere of heaven, “indergoading him on

to the vierge violetian.”

There is reason to believe that Dante had chronic eye troubles. Like Milton, who went blind

by excessive study, Dante sometimes strained his eyes by “[p]oring over manuscripts late

into the night by candlelight, as well as [by] naked-eye gazing at the stars.” In Il Convivio, after discussing at length the Aristotelian diaphane, to which Stephen Dedalus refers in the

“Proteus” episode of Ulysses, Dante lists the painful experience of temporarily losing his sight

as a result of an intense period of reading:

[B]y greatly straining my vision through assiduous reading I weakened my visual spirits

so much that the stars seemed to me completely overcast by a kind of white haze. But by

resting at length in dark and cool places and by cooling the surface of my eyes with clear

water, I regained that power which had undergone deterioration, so that I returned to my

former state of healthy

vision. Interestingly, Dante’s description of his convalescence closely resembles the incapacitating

blindness Joyce repeatedly suffered from during the strenuous materialization of Ulysses. At

such relapses of his earlier ophthalmological symptoms like iritis and glaucoma, Joyce, in

fact, would lay immobilized in a darkened room, while Nora generally would stay at his side, “dipping a cloth into ice water and applying it to his eyes.” Apart from the fact that Dante

occasionally overstrained his eyes by excessive study, it remains unclear whether he, like

Joyce, suffered from a visual impairment that reached deplorable proportions. In any case, the

Florentine poet’s real or imputed eye troubles, added to the recurrent theme of occluded and

remediated vision in the Divina Commedia, underlines his distinct association with the

literary tradition of the blind bard.

Comparable with the pilgrim Dante who, deprived of outer light, looks at the inner light of

divinity through the eyes of Beatrice, the blind bard in the third book Milton’s

Paradise Lost, through the medium of the heavenly muse, “may inhabit a landscape he cannot see and can be

invited into the celestial vision that none of the seeing world can directly experience.”

Drawing upon extremely personal references, since his own eyes would “roll in vain / to find

[God’s] piercing ray and find no dawn,” John Milton, in the so-called “Hymn to Light” at

the beginning of Book Three, “is using his own biography to develop the principal themes of

the digression, relating the paradoxes of deprivation of light to the hymn’s salutation to

Celestial Light.” Evoking the figure of Maeonides (Homer) and emphasizing their

biographical convergence, Milton creates a blind bard who, like the pilgrim Dante, “is a

visitor to the realms of Chaos and Eternal Night, returned safely to the realms of light.” In

line with the sharpened inner vision that traditionally compensates the visually impaired bard

or seer, Milton further invokes the Celestial Light to “shine inward and the mind through all

her powers / irradiate; there plant eyes; all mist from thence / purge and disperse, that I may

see and tell / of things invisible to mortal sight.”

As stated before, the theme of blindness has become a twofold expression in the literary

tradition. Especially with the definition of the Romantic ideology of poetic vision, “the topics

of blindness and second sight [became] closely linked.” As Patricia Novillo-Corvalán puts

it, “[w]hat the unseeing, inert eyes of the poet cannot perceive is compensated for by the vast, unlimited vision afforded by the eye of the imagination, as the poet exchanges eyesight for the

craft of versifying.”

In Romanticism, the seer might therefore be easily confused with the

bard, since the prophetic or poetic vision attributed to the artist immediately relates to divine

inspiration or inspired divination.

Apart from the literary tradition of the blind bard, which originated with Homer, Joyce’s

physical blindness as an appropriate indicator of his poetic vision has a distinct cultural

background much closer to home.

In “The Celtic Bard of Romanticism,” Edward Larrissy, in

fact, states that the topics of physical blindness and ‘second sight’ have been associated with

the Celtic bard since the early eighteenth century, even before the appearance of

MacPherson’s Ossian. According to Larrissy, “Irish tradition played a small but indubitable part in fashioning the image of the visionary, and sometimes blind, bard.”

The belief in

‘second sight,’ furthermore, “was part of the common inheritance of Ireland,” as famously

rendered by Synge’s Riders to the Sea or Yeats’s folklore writings.

The present study, in short, will not attempt to trace Joyce’s literary precursors or any

precedent for the sightless poet in English literature or elsewhere, for that would be an

unending task.

Apart from the fact that the important literary relationship between Joyce and

respectively Homer, Dante, and Milton clearly lies beyond the scope of this thesis, various

scholars, furthermore, have already explored a range of (intertextual) connections and

formulated, through detailed parallel readings, significant theories of influence and

intertextuality.

In the light of Joyce’s progressive eye troubles and his related affiliation with

the literary tradition of the blind bard, this study will neither attempt to recover his private

thoughts on these matters. We shall be concerned, instead, with Joyce’s explicit references to

the topics of (figurative) blindness and myopia in his literary work, and especially with the

sensory apparatus in Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. Rather than touching upon matters that

have really been worked into the ground, such as the use of music or the aural mode in

Joyce’s later prose fictions, or copying a simple study of influence from authoritative critical

contributions, I will attempt to unearth a relatively new field of study in which blindness as a

twofold expression constitutes a framework for the thematic discussion of Joyce’s occluded

vision.

ϟ

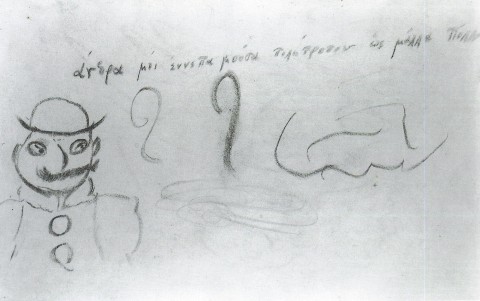

In January 1926, to demonstrate his improving

vision, Joyce picked up a thick black pencil and made a few squiggles on a sheet

of paper, along with a caricature of a mischievous man in a bowler hat and a

wide moustache –Leopold Bloom -, the protagonist of

Ulysses.

-

c1888: (6

years old)

glasses

prescribed

for

nearsightedness

(broken but

replaced)

He had tried

to spell out

the headline

for himself

though he

knew already

what it was

for it was

the last of

the book.

Zeal without

prudence is

like a ship

adrift. But

the lines of

the letters

were like

fine

invisible

threads and

it was only

by closing

his right

eye tight

tight and

staring out

of the left

eye that he

could make

out the full

curves of

the capital.

[in

"A Portrait

Of The

Artist As A

Young Man"]

-

c1894: (12

years old)

advised by

'foolish

doctor' to

put aside

glasses (Richard Ellman 26)

/ school

medical

officer (Peter

Costello

129)

-

1904 June:

can't tell

if it's Nora

at

rendezvous

-

1905 Feb to

Stannie: "I

was examined

by the

doctor of

the Naval

Hospital

here last

week and I

now wear

pince-nez

glasses on a

string for

reading. My

number is

very strong

-- could you

find out

what is

Pappie's." [E192]

-

1907 Jul:

rheumatic

fever

initiates

eye problems;

Lucia named

after patron

saint of

eyesight

(E262, 268)

-

1908: iritis

(Costello

276)

-

1909 Dec:

iritis in

Dublin (Costello

290)

-

1910:

drinking in

Pirano (near

Trieste)

later blamed

for eye

problems

(E535)

-

1917 Aug:

attack of

glaucoma,

insensible

with pain

for 20min,

iridectomy

by Sidler on

right eye

for

glaucoma,

exudation

permanenty

reduced

vision

(E417)

-

1918 Jul:

iritis

returns in

both eyes,

almost

incapacitated

for a week

or more "dangerously

ill and in

danger of

blindness"

(E442)

-

1918 Nov:

eye troubles

recur

-

1919 Feb: "my

eyes are so

capricious...

This time

the attack

was in my

'good?' eye

so that the

decisive

symptoms of

iritis never

really set

in. It has

been light

but

intermittent

so that for

five weeks I

could do

little or

nothing

except lie

constantly

near a stove"

(E454)

-

1921 Jul:

five weeks

recuperating

from iritis

attack w/cocaine,

lying in

darkened

room, came

to a head in

three hours

(E517)

-

1921 Aug: "I

write and

revise and

correct with

one or two

eyes about

twelve hours

a day I

should say,

stopping for

intervals of

five minutes

or so when I

can't see

any more."

(E517)

-

1922 May:

iritis

recurs,

spread to

left eye

(E535) "a

furious eye

attack

lasting

until [October]"

(E538)

-

1922 July :

Berman

advises

complete

extraction

of teeth

(E536)

-

late 1922:

everything (or

eyes

themselves?)

looks red

(E537)

-

1922 Oct :

leeches and

dionine from

Dr Collin

(E538)

-

1923 Apr:

teeth

extracted,

Borach

performs

sphincterectomy

on eye,

unable to

read until

June (???)

(E543)

-

1924 Apr:

Borsch

notices

secretion

forming in

conjunctiva

of left eye

(E564)

-

1924 June:

second

iridectomy

on left eye,

nightmarish

visions

after (E566)

-

1924 Jul:

eyepatch

(E567)

-

1924 Nov:

sight dims

again,

cataract

removed from

left (E568)

-

1925 Feb:

conjunctivitis

in right,

pain,

leeches and

morphine

(E569)

-

1925 March:

fresh

trouble in

right "one

eye

sightless

and the

other

inflamed"

(E570)

-

1925 April:

operation on

left, slight

return of

vision;

right can

read print

w/magnifying

glass (E570)

scopolamine

treatments

-

1925 Aug:

sight too

poor to walk

on beach

(E572)

-

1925 Oct:

eyes better

(E573)

-

1925 Dec:

operation on

left, quite

blind after

(E573)

-

1926:

switches to

large

writing

(E573)

-

1926

spring-summer:

eyes better

ϟ

excerto de:

Joyce’s

Myopia, Irisitis, and

Blind Prophecy

autor: Jan Leendert van

Velze

Dissertação em

Literatura Comparada

Universidade de

Utrecht, Holanda

17.Jan.2012

Publicado por

MJA

|