|

|

excerpt

AWAKENING in the predawn darkness, I grope among the anguished remnants of

dreams that linger in my consciousness, in search of some ardent sense of

expectation. Seeking in the tremulous hope of finding eager expectancy reviving

in the innermost recesses of my being—unequivocally, with the impact of whisky

setting one’s guts afire as it goes down—still I find an endless nothing. I

close fingers that have lost their power. And everywhere, in each part of my

body, the several weights of flesh and bone are experienced independently, as

sensations that resolve into a dull pain in my consciousness as it backs

reluctantly into the light. With a sense of resignation, I take upon me once

more the heavy flesh, dully aching in every part and disintegrated though it is.

I’ve been sleeping with arms and legs askew, in the posture of a man reluctant

to be reminded either of his nature or of the situation in which he finds

himself.

Whenever I awaken I seek again that lost, fervid feeling of expectation, the

ardent sense of expectation that is no consciousness of lack but a positive

actuality in itself. Finally convinced that I’ll not find it, I try to lure

myself down the slope to second sleep: sleep, sleep!—the world does not exist;

but this morning the poison tormenting my body is too virulent to permit retreat

into slumber. Fear threatens to engulf me. Sunrise must be at least an hour

away; till then, there’s no telling what kind of day it will be. I lie in the

dark, knowing nothing, a fetus in the womb. There was a time when sexual habits

were useful on such occasions. But now at twenty-seven, married, with a child

put away in an institution, I feel shame welling up at the idea of masturbation,

stifling the buds of desire. Sleep, sleep !—if you can’t sleep then pretend

you’re asleep. Suddenly, in the darkness, I see the square hole the workmen dug

yesterday for our septic tank. In my aching body the desolate, bitter poison

multiplies, threatening to ooze out slowly, like jelly from a tube, from ears,

eyes, nose, mouth, anus, urethra. . . .

Still in the guise of a sleeper, with eyes closed, I stand up and move

sluggishly through the darkness. Each time I hit some part or other of my body

against the door, the wall, or the furniture I give a painful, half-delirious

moan. My right eye, admittedly, has no sight even wide open and in broad

daylight. I wonder if I’ll ever know what lay behind the events whereby my eye

got like that. It was a nasty, stupid incident: one morning, as I was walking

along the street, a group of primary school children in a fit of hysterical fear

and anger flung a chunk of stone at me. Struck in the eye, I lay where I fell on

the sidewalk, unable to make out what had happened. My right eye, with a split

extending horizontally from the white into the black, lost its vision. Even now,

I’ve never felt I understood the true meaning of the incident. Moreover, I’m

afraid of understanding it. If you try walking with one hand over your right

eye, you’ll realize just how many things lie in wait for you ahead on the right.

You’ll collide with the unexpected. You’ll strike your head and face repeatedly.

Thus the right half of my head and face has never been without some fresh mark

or other, and I’m ugly. Even before the eye injury I was already showing more

and more clearly a quality of ugliness that often reminded me how mother had

prophesied that, when we grew up, my brother would be handsome and I would not.

The lost eye merely emphasized the ugliness each day, throwing it into constant

relief. My born ugliness would have liked to hang back, silent, in the shadows;

it was the missing eye that continually dragged it out into the limelight. Not

that I neglected to assign a role to this eye : I saw it, its function lost, as

being forever trained on the darkness within my skull, a darkness full of blood

and somewhat above body heat. The eye was a lone sentry that I’d hired to keep

watch on the forest of the night within me, and in doing so I’d forced myself to

practice observing my own interior.

Passing through the kitchen, I feel for the door, go out, and finally open my

eye to find the faintest whiteness spreading over the distant heights of a

leaden, late autumn, predawn sky. A black dog comes running up and jumps at me.

But instantly it knows itself rejected; without a sound it shrinks back into

stillness and stands pointing its small muzzle at me like a mushroom in the

darkness. Picking it up, I tuck it under my arm and walk slowly on again. The

dog stinks. It remains still under my arm, panting heavily.

My armpit gets hot. Perhaps the dog has a fever. The nails of my bare toes

strike a wooden frame. I put the dog down for the moment, grope about to check

the position of the ladder, then encompass with my arms the darkness at the spot

where I set the dog down; it still occupies precisely the same space. I can’t

help smiling, but it’s not a smile that lasts long. The dog is sick, for

certain. Laboriously I climb down the ladder. There are puddles here and there

at the bottom of the pit, enough to cover the ankles of my bare feet: just a

little water, like juices pressed from flesh. Sitting down directly on the bare

earth, I feel the water seeping through my pajama trousers and underwear,

wetting my buttocks, but I find myself accepting it docilely, as one who cannot

refuse.

Yet a dog, of course, can refuse to get dirty. The dog, silent like one that can

talk but chooses not to, perches on my lap, leaning its shivering, hot body

lightly against my chest. To preserve this balance, it sets hooked claws into

the muscles of my chest. I feel the pain as yet another thing that cannot be

rejected, and in five minutes am indifferent to it. I’m heedless, too, of the

foul water that wets my buttocks and comes seeping in between my testicles and

thighs. My body—all 154 pounds and five feet six inches of it—is no different

from the load of soil that the laborers dug yesterday from this very spot and

discarded in some distant river. My flesh is assimilated by the soil. In my body

and the surrounding soil and the whole damp atmosphere, the only signs of life

are the dog’s heat and my nostrils. The nostrils become rapidly sensitive, and

absorb the restricted smells at the bottom of the pit as though they were of

unutterable richness. Functioning at full pitch, they assimilate odors too

numerous to recognize individually. Almost fainting, I bang the back of my head

(and feel it directly as the back of my skull) against the wall of the hole,

then go on, indefinitely, absorbing the thousand and one odors and what little

oxygen is available. The desolate, bitter poison still fills my body, but no

longer seems to be seeping through to the outside. The ardent sense of

expectancy hasn’t yet returned, but my fear has been alleviated. Now I’m

indifferent to everything; indifferent, even, to the very possession of a body.

My only regret is that there is no one and nothing to observe me in my total

indifference. The dog? The dog has no eyes. Nor have I eyes in my indifference.

Since I reached the bottom, my eyes have been shut again.

ϟ

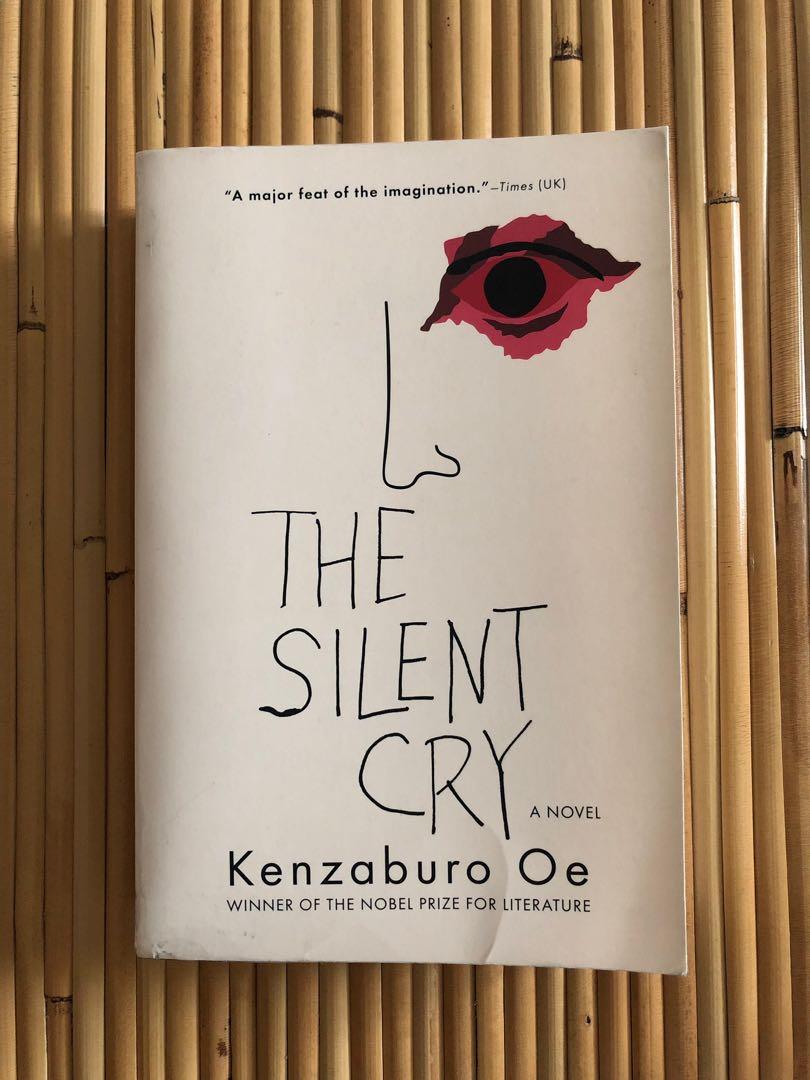

Born in 1935, Kenzaburo Ōe is the leading Japanese writer of his generation. He

spent the sixties in Paris where he came under the influence of Sartre. Winner

of the 1994 Nobel Prize for Literature, Kenzaburo Ōe is one of the great writers

of the twentieth century. When he was awarded the Nobel Prize, The Silent Cry

was identified as his key work. The Nobel Committee stated that ‘his poetic

force creates an imagined world, where life and myth condense to form a

disconcerting picture of the human predicaments’.

THE SILENT CRY

-excerpt-

Kenzaburo Ōe

Copyright © 1967 Kenzaburo Ōe

Translated by John Bester

23.Mar.2023

Publicado por

MJA

|