|

|

Lucia Reily

Antoine Coypel

Introduction

Advances in educational policies worldwide have contributed to achieving more equal educational and

professional opportunities for visually impaired children and adults. However, many age-old

myths on

blindness continue to be incredibly tenacious, affecting attitudes towards the blind and relationships in

inclusive contexts. In helping readers to reflect upon myths we seem never to outgrow, our intention is

to work towards a more inclusive society for people with visual disabilities. Understanding how

representations are socially constituted and developed, how they are revealed and how they are

disseminated should aid those interested in changing conceptions of disability that have crystallized

over time.Conceptions of disability, including attitudes towards blindness, are social constructions. Simi Linton

(1998) argues that the Arts have an important role in “breaking down stereotypes through the analysis

of metaphors, images, and all representations of disability in the academic and popular cultures.” (p.142).

She explains that understanding the meanings and functions of symbolic and metaphoric

representations of disability will help to subvert their power. “We need to trace patterns in the use of

metaphors and in symbolic uses of disability to determine where and how they emerge, and how they

function in various genres, cultures and historical periods” (p. 129). This investigation is a step in that

direction.

Objectives

Our aim is to investigate conceptions of disability revealed in Western artworks from the Middle Ages

to the present, as a contribution to understanding how collective attitudes towards blindness have been

shaped and maintained in our society 1 . Analyzing representations of disability in Western art helps us

understand the processes by which stereotypes of difference have been socially and historically

constructed, for not only do images reveal social conceits, but they also have a role in molding

society’s views of difference and/or deviance (Gilman, 1994). As we dig out subliminal messages that art works transmit, hopefully we can become less vulnerable to interpretations of disability that

permeate social discourse. Another objective is to make available our data bank of depictions of

blindness in Art History.This study is based on Gilman’s (1985, 1994) view that artists reflect prevalent attitudes of society as

they reshape stereotypes through visual portrayals of disability. By means of a circular dynamic, artists

express collective conceptions, which in turn contribute to their contemporary’s attitudes towards

disability. No matter how original and creative each artwork might be, there are never entirely

individual expressions; all representations speak for the collective (Wertsch,1991).

Finding representations of blindness

Our first sources were art history books on artists known to have represented the blind, for whatever

reasons. From these first entries, we broadened our findings through various internet search engines

and art museum sites, using key words such as “blind”, “blindness”, “cane”, “miracle”, “healing”,

“cure”, “beggar”, “alms”. By this means we came upon works by other artists such as Ribera, Poussin,

David, Barlach, Ernst, and Bourgeois, all of whom visited the theme of disability again and again.

Using links to art museums in Europe, North America and Brazil, many of the artworks can be viewed in

ArteEmComum, under the topic Representações.

Our intention in discussing the 115

images is to present an overview so as to characterize attitudes of specific periods of time.

An iconography of blindness

As we looked for artistic representations of visual impairments, we soon discovered that representing

blindness is quite challenging, since not seeing is an abstraction, it’s not a definite physical trait. Signs

for physical disability, such as wheelchairs, crutches, braces, peg legs, canes, or prosthetic limbs, are

much easier to identify. Eyes, on the contrary, are mere details in a painting. As we analyzed the

reproductions, it became apparent that artists used various solutions in their portrayals to help the

public identify blindness in their portrayals. Ginzburg (1989) was an important methodological aid for

this analysis.The title might contain explicit references to blindness or clues to be confirmed in the picture itself. References to blindness in the title are especially helpful in modern and contemporary non figurative

art forms, i.e. works by Ernst 2 or Bourgeois 3 .

nota: clique nas miniaturas para ver as imagens maiores.

|

|

|

2.

The blind swimmer,

Max Ernst, 1934 |

3.

The blind leading the blind,

Louise Bourgeois |

Many artists count on subtexts, such as the viewers’ knowledge of myths (Tiresias 4 , Orion 5 , the blind

Minotaur 6 ),

|

|

|

|

4.

Manto and Tyresias.

Henry Singleton,

exhibited 1792 |

5.

Blind Orion Searching

for the Rising Sun,

Nicolas Poussin 1658 |

6. Blind minotaur led by

a young girl at night,

Pablo Picasso, 1934 |

characters from the Bible (Old Isaac 7 , Jeroboam 8 , Tobit 9 , the blind men of Jericho 10 )

|

|

|

|

|

7. Isaac and Jacob,

Jusepe de Ribera, 1637

|

8. Jeroboam’s wife

visits the

prophet Ahijah,

Frans van Mieris

the Younger, 1671

|

9.

Anna and the

Blind Tobit,

Rembrandt, c1630 |

10.The blind of Jericho,

Nicolas Poussin, 1650 |

or

historical figures (Homer 11, Milton 12, and the Roman general Belisarius 13 ).

|

|

|

|

11. The Apotheosis of Homer,

Jean Dominique Ingres, 1827

|

12. Blind Milton reciting

his poem Paradise Lost

to his

daughters,

Laure Jules

|

13.

Belisarius recognized

by a soldier,

Jacques Louis David, 1781 |

However what we found

most interesting were visual clues invented by Medieval artists, and revisited by later artists, who collaborated in building an iconography of blindness.

We encountered blindness represented figuratively in:

-

Eyes closed/eyes opened after healing; whitened eyes, empty sockets; prosthetic eyes,

asymmetry of eyes or direction of gaze; vacant stares;

-

Use of dark glasses, thickened lenses, optical devices, blindfolds;

-

Indication by pointing, showing or touching eyes;

-

Postural clues: uplifted heads; arms held out, with open hand feeling or scanning the air;

unsteady stance, with one foot forward stepping gingerly;

-

Prostrate body; bedridden figure; seated unoccupied figure as opposed to someone working next to him/her;

-

Presence of cane, stick or musical instrument;

-

Exaggeration of hand size; hands feeling;

-

Presence of helper, guide, child or dog, leading the blind person;

Historical overview

Analyzing 115 works from Western art collections, we found that over 50% pertain directly or

indirectly to religious contexts, where blindness is depicted as punishment for wrongdoing, as

opportunity for doing good works, as evidence of man’s weakness before God, as proof of the power of

divinity over flesh. Only 5 of the 60 images we found from Medieval art through the XVII century

were not religious representations.

Medieval pictorial representations mostly fall under the category of illustrations. Although we have

not as yet encountered stained glass windows, religious sculpture, altar paintings or church triptychs

showing disability, we did find references to a number of illuminations and a few paintings in Medieval

Art. In many of these the artist is unknown, and the images complement written texts (psalters,

breviaries, the Gospels, lives of saints), with a didactic intent. These depictions are small – sometimes

drawn inside an initial.By the Renaissance, artists have gained professional status. Artworks seek independence from

religious texts, even though they still depict many of the same religious themes. But now, narrative

drama is more fully explored in the pictorial solutions that are sought, along with a growing

preoccupation with anatomical proportion and representation of depth. Given the preoccupation with

ideal beauty and rediscovery of Greek and Roman Art of the Renaissance artists, we did not expect to

find many representations of the disabled, but, in fact, many major artists did touch upon this theme.

Due to the way society was organized, with enormous power in the hands of the church, many

paintings were ordered from studios for religious functions. It is surprising to find so many portrayals

of disability in a society seeking aesthetic harmony and repudiating deformity. However, Christians

were expected to do good, as a means of obtaining forgiveness for sins, in this life or in the afterlife, so

almsgiving to mendicants (who were often disabled and dependent on society for survival) served as a

means for furthering Christian ideals. Portrayals of the disabled were good reminders of what was

expected of the faithful.The seventeenth century witnesses the birth of a new scientific outlook on life; the senses are viewed as

the main source of knowledge, so loss of sight provokes new interest in artists. How can you know if

you can’t see? Ribera 14 is one of the major artists interested in this subject.

|

|

14. The sense of Touch,

Jusepe de Ribera, 1615-1616

|

14. Blind old beggar,

Jusepe de Ribera, 1632

|

As ideals of beauty that characterized Renaissance art give way to observation of facts, the common man begins to show his

face. Here we have Rembrandt’s genre etchings of blind men and of crippled beggars. He studied

actual people on the streets, and later included them in his major compositions of religious themes.

Rembrandt revisits the theme of blindness in the story of Tobit a number of times 15 , portraying a

different moment in the life of this man and his family in each artwork.

Tobie guérissant

son père de la cécite

Rembrandt, 1636

|

The blind Tobit

Rembrandt, 1651

|

Anna and the

Blind Tobit,

Rembrandt, c1630

|

La guérison de Tobie

[esquisse]

Rembrandt

|

Though he was illustrating a

Bible story, he was also reflecting on the meaning of blindness in his own time.

We were surprised to find 8 works representing the blind in the Neoclassical period, all of them from

the second half of the eighteenth century. This period moves away from religious art as artists go back

to classical themes. The Roman general Belisarius 16 is a favorite, though Homer and Tiresias are also

portrayed.

|

|

|

16.

Belisarius recognized by a soldier,

Jacques Louis David, 1781 |

The Blind Prophet Tiresias

with the Baby Narcissus

Giulio Carpioni, after 1666

|

With moralistic undertones, many of these works speak of overcoming hardship, and of

feelings of pity of those who come to offer succor. Goya is an eighteenth century artist in a totally

different league. His paintings include all sorts of social misfits, such as the “Blind guitarist” 17. He is a

precursor to the expressionists and social injustice artists encountered in the twentieth century.

17. Blind Guitarist,

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, 1778

Romanticism is a ripe period for portraits of blindness, reflecting the patronizing and pitying attitudes

characteristic of society 18 .

18. The Lollipop,

James Campbell, 1855

We found 25 artworks for this period, many depicting models who defeated

blindness through achievements in poetry and philosophy. Though blindness is associated with frailty

and dependence, compensation is advocated through enhance-ment of hearing and tactile sensitivity as

well as musical skills 19 .

In many of these depictions, allegorical meanings are developed. Blindness

doesn’t refer as much to loss of sight as to loss of hope or loss of joy 20. As realism makes its dent in

romantic ideals, portraits of actual blind people begin to emerge 21 .

|

|

|

|

19. The Blind Fiddler,

Sir David Wilkie 1806

|

20. Hope,

George Frederic Watts

and assistants, 1886

|

21. Madame Renée de Gas,

Edgar Degas

|

The twentieth century greatly broadens pictorial possibilities for artists as artists abandon classical

themes and move away from naturalistic representations. There appears to be less interest in the

established iconographic schemes for blindness, as new forms of expression develop. There is a

surprising interest in blindness during the initial surges of Modern Art, including the stark criticism of

war by expression-ist artists such as Dix 22, or of family relationships 23, the dreamlike surrealist

depictions of Giorgio de Chirico 24 and Dali 25 ,

|

![O Vendedor de Fósforos [mutilado de guerra] - Otto Dix, 1921](https://www.deficienciavisual.pt/Quadros/TheMatchSeller-Otto%20Dix-1921_small.jpg) |

|

|

|

22. The blind match seller,

Otto Dix, 1920

|

23. Blind Mother,

Egon Schiele, 1914

|

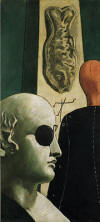

24. The nostalgia

of the poet,

Giorgio de Chirico, 1914

|

25. Debris of an Automobile Giving Birth

to a Blind Horse

Biting a Telephone.

Salvador Dali, 1938

|

works from Picasso’s blue period 26, American social militants

such as Shahn 27. Metaphoric representations link blindness to ignorance or to loosing one’s way 28 .

|

|

|

|

26. The blind man’s meal,

Pablo Picasso, 1903

|

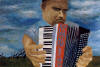

27. Blind accordion player,

Ben Shahn, 1945

|

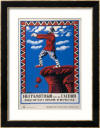

28. "The illiterate man is like a

blind man; failure and

misfortune

lie in wait

for him on all sides",

Alexeij A. Radakov, 1920

|

Portrayals of blind musicians 29 continue to appear among figurative artists, as do portraits of actual

people with visual impairments 30 .

|

|

|

20. Jazz Wall,

Marisol Escobar, 1962

|

21. Portrait of Wyndham Lewis,

Michael Ayrton, 1955

|

Attempts at interpretations of non figurative works are more

challenging, due to their polissemic nature, but verbal commentaries by twentieth century artists often complement their intentions.

Examining the conceptions portrayed

What do these representations reveal about conceptions of blindness? It is clear that different attitudes

predominate in different places and times, but some conceptions, such as dependency, vulnerability and

incapacity are never completely abandoned. The idea of disability as penalty, or punishment, dating

from Old Testament times through the Christian era, is revealed in the full time span of Western

artworks. As Spivey explains it: “For then scholars and ignoramuses alike knew the source of pain.

The Latin poena is perfectly parametered. It means ‘penalty’; it means ‘punishment’. (2001: p. 53)

How does the Bible portray the disabled? Miller and Miller (1952) explain that diseases and disabilities

were viewed as the result of sin:

-

punishment by God for a person’s own sins;

-

punishment

accorded to an innocent child for his parents’ sins; and

-

Satan’s seductive doings. Sometimes

misfortune just happens for no reason, as seen in the story of Job

(Old Testament) and in John (New

Testament).

Disability can occur arbitrarily, as in the story of Tobit, from the Books of the Apocrypha,

where Tobit 31, a righteous follower of Jewish law is struck blind, and is only cured many years later by

the Angel Raphael.

|

|

|

|

Tobias curing

his fathers blindness

Benjamin West, 1772

|

Tobias Heals His Blind Father

Annibale Carracci

|

The Young Tobias

Heals his Blind Father

Bernardo Cavallino, 1640

|

An insipient concern about disability rights appears in the Old Testament in Leviticus 19:14, where it is

forbidden to place tripping stones in the way of the blind. Those who purposefully make the blind

wander along the wrong pathway will be cursed, says Deuteronomy 27:18 (Miller and Miller, 1952).

One intriguing illumination shows a boy sipping soup from an unbeknownst blind man’s bowl, through

a long straw, revealing the vulnerability of the blind to trickery, and admonishing the boy for

wrongdoing.

Iluminura do século XIV que mostra como um moço de cego

furta a este o vinho por uma longa palha

Healings and miracles are the primary topics for depicting blindness in Medieval and Renaissance

artworks, as we see in Duccio 32 and Botticelli 33 .

|

|

|

32. Jesus opens the Eyes of a Man born Blind, Duccio, 1311

|

33. Three Miracles of Saint Zenobius

Sandro Botticelli, about 1500

|

In some works the theme is “doing good deeds”

(almsgiving), modeling what it means to be a Christian.

In such depictions, the blind are represented as

beggars, subject to the compassion of others. Some works function as visual literacy, illustrating

Biblical stories of the blind in the Old and New Testaments or of incidents in the lives of saints.

Sometimes the lesson has moral undertones, as in the powerful figure of Samson.

|

|

|

|

The Blinded Samson

Lovis Corinth, 1912

|

Samson at the Mill

Frederic Leighton, 1881

|

Sansão cego pelos filisteus

Rembrandt, 1636

|

Running through art history, depictions of blindness are used metaphorically, with negative

connotations, linking blindness to ignorance, hopelessness and to loosing one’s way, i.e. moving away

from God, most often permeated with a moral lesson of some kind. Dependent, vulnerable, or living in

poverty – being blind is often associated with frailty and dependence. Though sometimes portrayed as

incapacitated, unoccupied, unable to work, some artists focus on heightened sensitivity, and

compensation for loss of sight through enhancement of hearing and tactile sensitivity as well as musical

skills. Of the various kinds of disability we analyzed, only the blind are ever depicted working – as

poets, writers, philosophers or as musicians, playing the violin, guitar, accordion, or the harp.

In rare instances we did find representations of ordinary blind people, going about their daily lives, or

just sitting for their portrait, like anybody else. The representation of idealized blind men is more

common: depictions of worthy blind men such as Tobit or Belasarius who came into misfortune. In 6

such lay works, great men who were blind are shown overcoming their physical limitations,

compensating defeat through achievements in poetry, philosophy or music.

Although there appears to be a more healthy range of conceptions of blindness in the twentieth century

than in earlier periods, sadness, dependence and incapacity are still expressed in representations of our

times. Despite the force of social criticism of the German expressionists and American realists,

throughout modern and contemporary art, the blind continue to be portrayed mainly on the border of

society.

References

-

GARLAND, Robert. (1995). The eye of the beholder: deformity and disability in the Graeco-Roman

World. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

-

GILMAN, Sander L. (1994). Disease and representation: images of illness from madness to AIDS. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

-

GILMAN, Sander L. (1985). Difference and pathology: stereotypes of sexuality, race, and madness. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

-

GINZBURG, Carlo. (1989). Indagações sobre Piero: o Batismo; o Ciclo de Arezzo; a Flagelação. São

Paulo: Paz e Terra. Tradução de Luis Carlos Cappellano.

-

LINTON, Simi, (1998). Claiming disability: knowledge and identity. New York: New York University

Press.

-

MILLER, Madeleine S. & MILLER, J. Lane. (1952). Harper’s Bible Dictionary. New York: Harper &

Brothers, Publishers.

-

SPIVEY, Nigel. (2001). Enduring Creation: Art, Pain, and Fortitude. Berkeley, Los Angeles:

University of California Press.

-

TUPINAMBÁ, Ariane e REILY, Lucia. Relatório de pesquisa do Projeto “Retratos de deficiência e

doença mental: intersecções entre educação especial e história da arte. Revista de Educação

PucCampinas. Campinas, 16: junho, 2004, 127136.

-

WERTSCH, James W. (1991). Voices of the mind: a sociocultural approach to mediated action. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

NOTES

-

1 This study continues an earlier research project published in Tupinambá and Reily (2004).

-

2 The blind swimmer, Max Ernst, 1934, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

-

3 The blind leading the blind, Louise Bourgeois, 19471949, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

-

4 Manto and Tyresias. Henry Singleton, exhibited 1792, The Tate Gallery.

-

5 Blind Orion Searching for the Rising Sun, Nicolas Poussin 1658, Metropolitan Museum, N.Y.

-

6 Blind minotaur led by a young girl at night, Pablo Picasso, 1934, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

-

7 Isaac and Jacob, Jusepe de Ribera, 1637, Museo del Prado, Madrid.

-

8 Jeroboam’s wife visits the prophet Ahijah, Frans van Mieris the Younger, 1671, Musée des BeauxArts,

Lille.

-

9 Anna and the Blind Tobit, Rembrandt, about 1630, The National Gallery, London.

-

10 The blind of Jericho, Nicolas Poussin, 1650, Musée du Louvre.

-

11 The Apotheosis of Homer, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, 1827, Musée du Louvre.

-

12 Blind Milton reciting his poem Paradise Lost to his daughters, Laure Jules, Musée d’art et d’histoire, Lisieux.

-

13 Belisarius recognized by a soldier, Jacques Louis David, 1781, Musée Ingres.

-

14 The sense of Touch, Jusepe de Ribera, 16151616,

Norton Simon Museum; and Blind old beggar, Jusepe de Ribera, 1632,

Allen Memorial Art Museum.

-

15 Anna and the Blind Tobit, Rembrandt van Rijn, about 1630, The National Gallery, London.

-

16 Belisarius recognized by a soldier, Jacques Louis David, 1781, Musée Ingres.

-

17 Blind Guitarist, Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, 1778, Museo del Prado, Madrid.

-

18 The Lollipop, James Campbell, 1855, The Tate Gallery.

-

19 The Blind Fiddler, Sir David Wilkie 1806, The Tate Gallery.

-

20 Hope, George Frederic Watts and assistants, 1886, The Tate Gallery.

-

21 Madame Renée de Gas, Edgar Degas, 18721873,

National Gallery of Art, Washington.

-

22 The blind match seller, Otto Dix, 1920, Staadt Gallery, Sttutgart

-

23 Blind Mother, Egon Schiele, 1914 – Private Collection, Vienna.

-

24 The nostalgia of the poet, Giorgio de Chirico, 1914, Guggenheim Museum.

-

25 Debris of an Automobile Giving Birth to a Blind Horse Biting a Telephone. Salvador Dali, 1938, MoMa, New York

-

26 The blind man’s meal, Pablo Picasso, 1903, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

-

27 Blind accordion player, Ben Shahn, 1945 New

York, Roy R. Neuberger Collection

-

28 The illiterate man is like a blind man; failure and misfortune lie in wait for him on all sides, Alexeij A. Radakov, 1920,

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

-

29 Jazz Wall, Marisol Escobar, 1962, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago.

-

30 Portrait of Wyndham Lewis, Michael Ayrton 1955, The Tate Gallery.

-

31 Depictions of the various moments of the story of Tobit were tremendously popular all through art history, especially

during the Renaissance through Baroque Art (we found 19 representations of this story.

-

32 Jesus opens the Eyes of a Man born Blind, Duccio, 1311. The National Gallery, London.

-

33 Three Miracles of Saint Zenobius, Sandro Botticelli, about 1500, The National Gallery, London.

ϟ

Portrayals of the blind in art history: shaping conceptions of blindness

LUCIA REILY

Lecturer -

CEPRE, Faculdade de Ciências Médicas,

São Paulo, Brasil

Focus: Achieving equality in education: Attitudes and Policies

Topic: Personnel Preparation – teacher education and other professionals

Fonte do texto: ICEVI - International Council for Education of

People with Visual Impairment

Fonte das imagens:

A Cegueira Vista pela Arte

de Maria José Alegre

28.Mai.2011

Publicado por

MJA

|